Rich Grassi and I had a text-message discussion about our “early days” experiences with custom pistol smiths. We both became serious pistolero-aspirants in the mid 1970’s but took different paths; his, law enforcement, mine, “combat” (ultimately IPSC) competitive shooting. Rich suggested recording a few of the mishaps that were encountered -- along with lessons learned -- that readers of The Shooting Wire might be able to identify with, or at least find humorous.

Lesson One: Never be the first --

There’s truth to the maxim, “never buy the first iteration of any product.” The manufacturer will always work the “bugs” out on the second or third version which will be far superior to the first model.

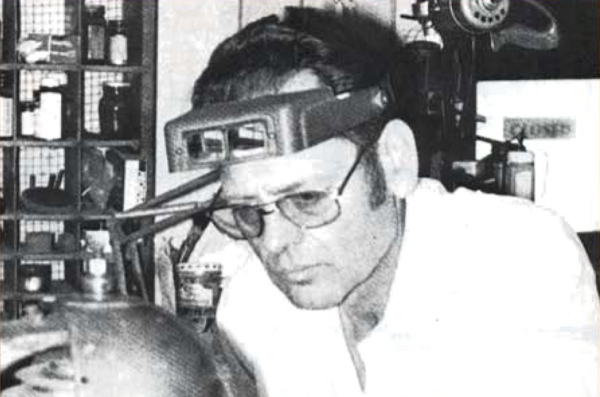

Case #1: In 1978, M-S Safari Arms began producing 1911’s equipped with features that many of the popular “custom” pistol smiths of the day were modifying or adding on to standard factory 1911’s. The most notable was their beavertail grip safety. At the time I was competing with guns built by Bud Price, Western Gun Exchange, Miami, Oklahoma. Bud was a wonderful craftsman and modest, which was uncharacteristic of some custom pistol smiths. I asked Bud if he could fabricate a “beavertail grip safety” for me; he had never seen one and asked me to describe it.

Keep in mind that there was no internet, cell phones and few personal computers in those days; there were only hard-copy magazines and snail mail. I drove to his shop and spent a day with him, showing him pictures of the Safari Arms beavertail. I asked that he not add the up-swept rear-tip of the safety, but just round it off (spoiler alert: that was a mistake). Time was critical as the 1979 IPSC Nationals were only a couple of weeks away and I wanted the grip safety in time for it.

True to his word, Bud had the piece completed just in time for the match but I’d have to pick it up the day before leaving for the competition. Bud installed it at his shop and the safety felt fine. A couple of days later when I shot the first event at the match, the grip safety cut into the web of my hand like it was a razor blade. By the end of that first relay my hand was a bloody mess. I spent the rest of the week shooting with my strong hand wrapped like an Egyptian mummy. The safety felt fine while gripping it but during recoil the radius on the bottom of the rounded-rear dug into my hand with the precision of a scalpel. When I returned home, I sent the gun to Bud and had a Safari-Arms safety installed -- which I should have done in the first place. It wasn’t Bud’s fault. He had followed my directions precisely. The next gun that I ordered from him came with a Safari-Arms safety as standard equipment! I wasted two days driving to Oklahoma and today, 46 years later, the scars on my hand are almost completely undetectable!

Case #2: In 1980, at the second Bianchi Cup, John Shaw shook up the practical pistol world by shooting a Jimmy Clark “Pin Gun.” That started the “compensator” craze. At the time, Lew Sharp was the Colt representative that lived in Louisiana and was a close confidant of Jimmy Clark. He was also a friend of mine. Lew had an unmodified Colt Gold Cup that, according to Lew, had the second Pin Gun barrel/weight assembly that Jimmy ever made, installed by Jimmy. Lew sold me the gun. Clark manufactured this first iteration Pin Gun by milling a Douglas barrel blank so that the front inch or so matched the outer configuration of the 1911’s slide and then “coned” it down in diameter and welded a chamber cut off of a G.I. surplus barrel. The machining and fitting and welding required to do that properly was astounding. The welded joint was a weak point in the design. About a year later, the weld on my gun separated. On subsequent versions of the Pin Gun, Jimmy substituted a piece of bar steel for the Douglas barrel blank and would thread the interior of the cone and screw it onto a threaded long barrel doing away with the welded chamber. There’s the moral of the story -- never get the first version of a product. But the story doesn’t end there.

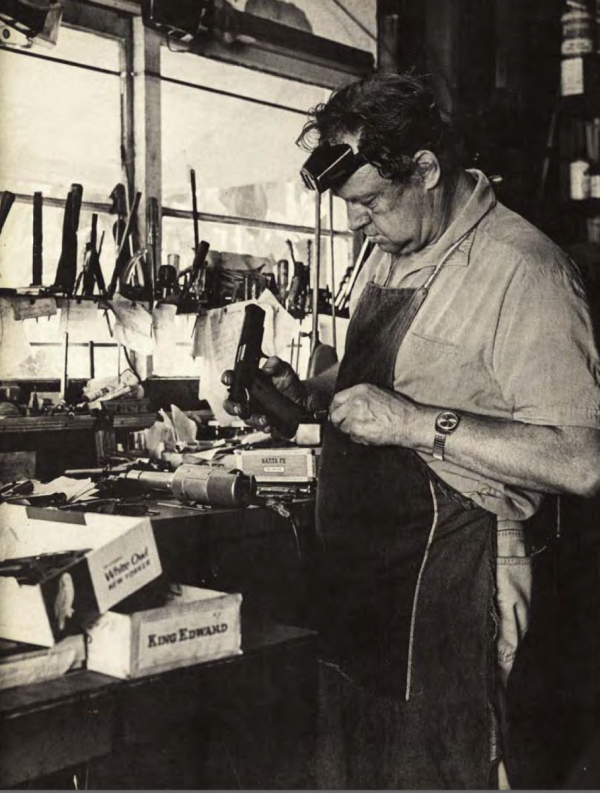

Although I was the IPSC Section Coordinator for Kansas, I regularly shot with the Midwest Practical Shooting League in Columbia, Missouri. About the time that my Pin Gun broke, I was approached by a fairly new shooter at an MPPL match that was a tool and die maker and had built himself a couple of competition pistols. He wanted to show me a compensator that he had designed and made and offered to build one for me. After shooting his, I was all in. I gave him the broken Clark Pin Gun and had him fit his compensator in its place on the Gold Cup. It was the second one that he had ever built; he called it a “Maxi-Comp,” and his name was Eddie Brown. That gun went from being Clark’s second Pin Gun to being Brown’s second Maxi-Comp. I was proud of that gun, heralded its virtues and let any interested bystanders shoot it. It became the “super-gun” at our local gun club. A couple of months and copious amounts of ammo later, the club ran a short “assault” course, the final shot of which was a stop plate at about 20 yards. I had shot my new super-gun well up until the stop plate. My first round hit low, the second round lower, the third hit the ground about halfway to the target! The compensator on my super-gun wasn’t exactly “dangling” off the end of the pistol, but it was at a 45-degree angle to the slide! I learned that bragging about your custom guns is akin to bragging about your bird dog’s retrieving skills or your children’s musical acumen, it will probably embarrass you. As I recall the autopsy report of super-gun, Eddie determined that the corpus delicti was that his comp was screwed onto the long barrel with too few threads that were cut too deep. All subsequent versions utilized shallower threads and more of them; and like almost all products, the following versions were superior to the first edition.

Lesson 2: What’s important to you, may be trivial to your gunsmith

A key person that shot with us in the early days of the Kansas Section of IPSC (1978 to about 1982) was Roy Erwin. Roy was “to the manor born,” intelligent, socially fearless and an all-around bon vivant. He was a multiple course graduate of early Gunsite (API) and was a fixture at the Chapman Academy. He shot only the finest rifles and handguns. Most memorable of his personal arsenal were four full-house, customized Armand Swenson handguns: two consecutively serial numbered Government Models, a Commander and the most beautiful Browning High Power that has ever existed. By “full-house” I mean that these guns had every feature that Armand offered: squared trigger guards, S&W K-frame sights, ambidextrous safeties, checkered frames, checkered slide backs, French cut, stippled top of the slide and hard chromed in an esoteric hue of light silver/gray that Ansel Adams never discovered. They were special.

When Dave Westerhout won the 1977 IPSC World shoot in Salisbury Rhodesia using a minor caliber, 9mm Browning High Power, there was a small but noticeable ripple that traversed through the American Region of IPSC. A number of U.S. competitors tried the 9mm (ultimately only Tommy Campbell stayed with the minor caliber gun). Bar-Sto came out with a 6” ported barrel for Browning High Powers with the intent of goosing the ballistics of the Parabellum high enough to make major caliber. I don’t know what the prevailing inspiration for Roy Erwin was, but he sent his High Power back to Armand to have a 6” ported barrel retro-fitted to his stunning Browning. When the gun was returned, it sported the long barrel, but also was equipped with a barrel bushing. Since the High Power has no recoil spring plug like the 1911, how the barrel bushing was held in place was a mechanical mystery.

Roy and I went to the range to shoot his reborn Swenson High Power. After shooting about half a box of cartridges the first problem manifested itself. The porting on the barrel was cut perpendicular to the bore axis and parallel to the crown about 1/4” back from the muzzle. Having two slots cut in the barrel results in a narrow “bridge” of uncut steel between the two narrow slots. That bridge had been blown out leaving one relatively large port instead of two small slots. It was at this point that we noticed that the Bar-Sto trade mark wasn’t engraved on the barrel hood. When Roy decided to take the gun apart to examine the barrel, the second problem manifested itself. Armand had sent no directions on how to disassemble the pistol with the Swenson-fabricated barrel bushing. Indeed a conundrum. We decided to call Armand for help. Fortunately, Roy had a speaker for his phone so I got to listen in on the interchange. To his credit, Swenson was perhaps the most popular and busy pistol smith in the world at the time and it became quickly obvious that this gun was a bespoke, one-off piece that Armand had done quickly and couldn’t remember the details. Roy asked him who the barrel manufacturer was. Armand hesitated and said, “It’s a ‘custom’ barrel Laddie.” (Swenson had the habit of calling everyone “Laddie.”) Roy asked again who made it and Armand repeated, “It’s a ‘custom’ barrel Laddie.” When Roy asked him how to remove the barrel bushing, Armand hesitated again then replied, “Describe it to me Laddie.” Roy and I were struggling to not laugh at that point. After describing the bushing, Roy asked him how he was going to clean the gun if he couldn’t remove the bushing to which Armand responded, “Well, just send the gun to me and I’ll clean it for you Laddie.” At that point the humor of the situation exceeded the frustration of the circumstances. Roy sent the gun back and I honestly don’t remember the resolution, but I still have that beautiful High Power seared into my memory along with the mirth of dealing with Armand.

None of the above is intended to be critical of Bud, Eddie or Armand. I knew, respected, and miss each of them. However, that doesn’t alter my advice when dealing with gunsmiths: try to never purchase the first edition of anything, and realize that what’s important to you may be trivial to them.

Editor’s note: Remember, in working with custom gunsmiths – as in all relationships -- communication is critical. It really should be easy these days …

- - Greg Moats