I suppose a good many readers of Shooting Wire are well aware of the nexus between the nation’s founding documents and current events. And that’s fair. Looking back to see where “it all started” is smart; we can see what situations set up the Revolution, what forces shaped the battle and its resolution and we can see the way to prevent having to do it all over again in the short term. That was the design of the Constitution – and its amendment via the Bill of Rights.

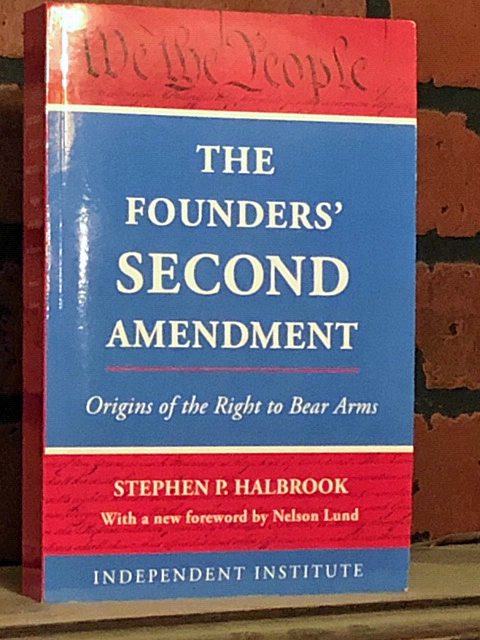

The mistake many make is reading the document with no grasp of its context. It takes into account only the actual language of the document without seeing (1) the situation that generated the war that preceded it, (2) the thoughts and ideas of the people drafting the document and (3) their intentions … their wishes for a future. Such a bald analysis disregards the arguments between those charged with creating the greatest country on Earth, a home for liberty that drew millions from other continents with the beacon of freedom. Where do you go to get the historical narrative and analysis? Right here: The Founders’ Second Amendment by Stephen P. Halbrook

Where did the idea for a “right to keep and bear arms” come from? Examining the America of 1768 through 1826 and the surviving declarations of the Founders helps; those pronouncements appear in newspapers, correspondence, debates and resolutions. This documentary evidence tells the tale of the America we had during the waning years of British rule, the Revolution, the adoption and amending of the US Constitution which came to include a Bill of Rights, and into the passing of the Founders’ generation.

This book is a history of the origin of the recognition of the individual’s right to bear arms in the United States of America. In this updated addition to The Founders’ Second Amendment: Origins of The Right to Bear Arms, the author examines the era in an attempt to explain the intent underlying the addition of the Second Amendment to the Constitution.

He goes through a history of the end of British colonial rule of the United States and discusses outrageous acts committed by British troops against colonials in Massachusetts and elsewhere. The examination of the various battles and how colonials pressed the battle with their own small is explored as is the aftermath of revolution.

Halbrook also surveys the impact of the constitutions of the individual states on the process of forming the United States Constitution, in particular the Bill of Rights. Apparently, some thought that the Bill of Rights was simply rehashing the struggle they’d just finished – that anyone with any sense would know that government must be limited by the power of the individual.

Sadly, we know now that’s not true. We can give thanks that there was a strong influence in the direction of spelling out individual human rights. It’s the frail reed that’s prevented us from thus far following the Empire of that time, the Commonwealth of the current era, down the statist, strong government trail.

Part of the discussion against a ‘bill of rights’ included the concept that ruling out infringements to powers the new country wouldn’t even have in their federal republic might imply that such “mission creep” was permissible. This was disputed by some writers – as shown below:

“There are certain unalienable and fundamental rights, which in forming the social compact, ought to be explicitly ascertained and fixed -- a free and enlightened people, in forming this compact, will not resign all their rights to those who govern, and they will fix limits to their legislators and rulers, which will soon be plainly seen by those were governed, as well as by those who govern.” – “Letter,” the second, dated October 9 (1787), from the “Federal Farmer.” (p. 185)

The analysis continues by an examination of the language used in the context of the era of the foundation of the States. This includes “arms,” “to keep, “to bear” --- and “infringed.”

“It is noteworthy that the Second Amendment proscribes any infringement, not just “unreasonable” infringement. Some guarantees are more relative then the others --for instance the Fourth Amendment proscribes only unreasonable searches and seizures. “(p. 329)

As it’s long established that laws be examined in the light of the intent of the legislature who wrote the law, this book is critical for any current discussion about gun rights in the United States of America. We’re faced with assaults on civil rights based on a vacuous intent to slow “gun violence,” something which doesn’t exist. Assigning culpability to artifacts when the law appropriately proscribes behaviors is ignorant – and popular with the low information crowd.

As we face the coming “long, dark winter” mentioned by the presumptive incoming federal executive who was unwittingly predicting the results of the republic’s end, it’s instructive to see what the designers of the republic faced, fought, repelled and built – and which, remarkably, lasted as long as it did.

This is always relevant and this book an important read; in the current state of the Union, it’s more so. Getting a grasp of Stephen Halbrook’s scholarship is a first step to being an informed member of the gun culture.

Get it, read it. Mark it up. Reread it later. It holds critical lessons for the future.

-- Rich Grassi